Rhino Results at CITES CoP19

December 8, 2022

The 19th meeting of the Conference of the Parties of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, also known as the CITES CoP, has wrapped up in Panama City, Panama. Nina Fascione, executive director, and CeCe Carter Sieffert, chief conservation director, represented the International Rhino Foundation (IRF) at the meeting, joining more than 2,500 attendees to review and discuss proposals that govern the protection of wild animals.

For a brief overview of CITES, the CoP, and what it means for rhinos, please visit our blog post here to learn more.

Two proposals directly related to rhino conservation were discussed and voted on at the CoP. IRF is pleased to provide you the following wrap up, including the final vote results for the rhino proposals.

Rhino Proposal One: Namibia’s White Rhinos

Namibia and Botswana proposed the first rhino amendment, which sought to “downlist” Namibia’s white rhino population from Appendix I to Appendix II “For the exclusive purpose of allowing international trade in: a) live animals for in-situ conservation only; and b) hunting trophies. All other specimens shall be deemed to be specimens of species included in Appendix I and the trade in them shall be regulated accordingly.”

A species’ listing within an Appendix is based on how threatened the species is with extinction; Appendix I species are the most endangered and trade is only permitted in the case of non-commercial exceptions, such as research. Appendix II species can be traded, but with controls in place to ensure that trade does not lead to increased risk of extinction. Namibia and its supporters argued that the population of white rhinos within Namibia no longer meets the criteria required for Appendix I listing and that the population is currently increasing.

The Parties opposing this downlisting expressed several concerns, including the lack of clarity about how hunting would impact the population, fear that opening trade would create undue management burdens, and worries that the ongoing poaching crisis in other countries could spill over into Namibia, among others.

In response, the European Union proposed that trade be limited to translocation to in-situ (in their natural habitat) locations within “the natural and historical range in Africa” and that the inclusion of trade for hunting trophies be removed. This adapted proposal was voted on, with 83 Parties voting in favor, 31 Parties against, and 13 Parties abstaining. The proposal was accepted and Namibia’s white rhino population is now listed as an Appendix II species with the annotation that trade is “for the exclusive purpose of allowing international trade of live animals for in-situ conservation only, and only within the species’ natural and historical range in Africa. All other specimens shall be deemed to be specimens of species included in Appendix I and the trade in them shall be regulated accordingly.”

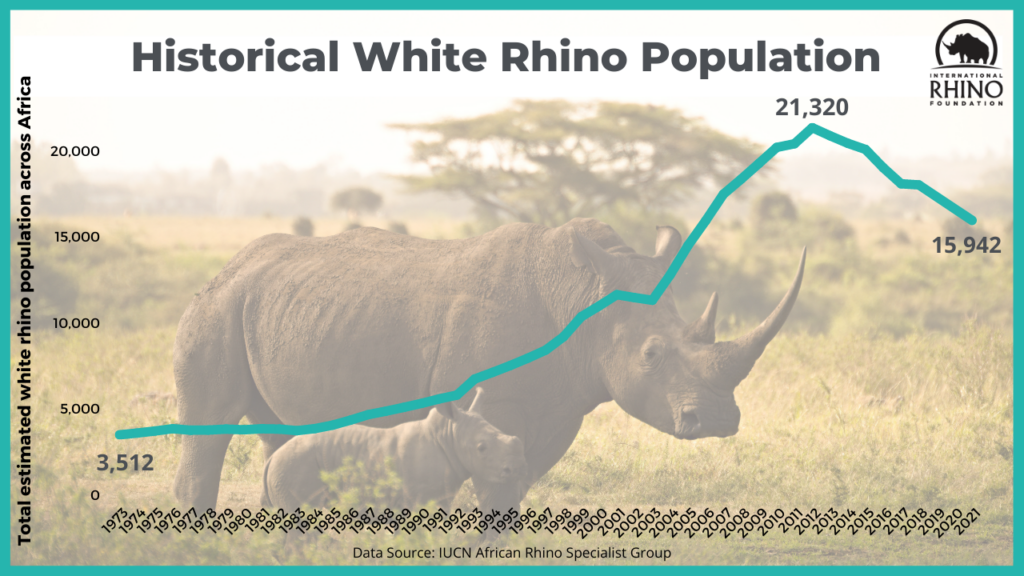

As a nonprofit organization, IRF attends the CITES meeting as an Observer and is not a voting member. However, we believe the vote on this amendment reflects a global recognition of Namibia’s successful efforts to protect and grow its white rhino population. Translocations of the species to its natural and historical ranges is an important tool to restore rhino populations as well as the habitats that evolved with them. The northern white rhino (Ceratotherium simum cottoni) is functionally extinct, with two remaining non-reproductive females living in Kenya. However, conservation efforts have begun to translocate southern white rhino (Ceratotherium simum simum) individuals, whose population currently stands at 15,942 as of 2021 (IUCN African Rhino Specialist Group report), to areas within the historic range of northern white rhinos with the intention of returning an ecological equivalent back to an environment.

Proposal to downlist Namibia’s white rhinos:

APPROVED WITH AMENDMENTS, 83 to 31; 13 Parties abstained

Rhino Proposal Two: Eswatini’s white rhinos

Eswatini proposed the second rhino-focused amendment, which sought to remove the annotation tied to the Appendix II listing of its white rhinos. The annotation states that trade in white rhinos (Ceratotherium simum simum) must be restricted to “the exclusive purpose of allowing international trade in live animals to appropriate and acceptable destinations and hunting trophies. All other specimens shall be deemed to be specimens of species included in Appendix I and the trade in them shall be regulated accordingly.”

Removing this annotation would allow Eswatini to engage in commercial trade of rhino horn and its derivatives. Acknowledging the risks associated with legalizing trade in rhinos, Eswatini proposed adding language that “An 18-month delay in exercising such an annotation removal shall apply to give the CITES Secretariat and identified trading States time to ensure that all trade control mechanisms are properly and transparently negotiated and implemented. Such oversight shall apply to every consignment’.

Eswatini is a small kingdom, surrounded on three sides by South Africa and highly dependent on South Africa’s economy and political stability. When COVID-19 forced many countries, including South Africa, to restrict all tourist entries, all the tourism revenue on which most of Eswatini’s conservation efforts rely came to an abrupt halt. Eswatini argued that engaging in commercial trade would help compensate for necessary lost conservation revenue. They pointed out that they have been successful in the fight against rhino poaching; since 1993 Eswatini has only lost three rhinos to poaching while across Africa 11,000 rhinos have been poached in the past decade. Eswatini clarified that the horn would be collected from rhinos who die of a natural death, from a poaching event, or is harvested using non-lethal methods, and that the sale of horn would cover the high costs of protecting the kingdom’s wild rhino population. They stated: “there would be no need to kill even one rhino in order to sustainably satisfy the currently known market.”

Opponents to the proposal countered with concern that any legal trade in rhino horn would be detrimental to the five global species, increasing trafficking of horn from countries other than Eswatini and complicating the already challenging effort to regulate existing trade laws. Eswatini requested alternative opportunities to support the ever-increasing cost of protecting rhinos, stating that providing “no alternatives is unfair, unjust and not in the long term interest in these species we protect.”

The Parties then voted on Eswatini’s proposal with 15 in favor, 85 against, and 26 abstentions. IRF supports this decision. While Eswatini has done an exemplary job protecting and growing its black and white rhino populations, it is critical that any consideration of the legalization of trade must first meet significant criteria such as increasing transnational cooperation and coordination for fighting illegal wildlife trade, addressing and reducing opportunities for corruption at all levels, and strengthening the prosecutorial impact of wildlife crime sentencing, among others. It is critical to use the precautionary approach for this issue; we must be certain that legalizing trade in rhino horn would only be considered if proven to directly benefit rhinos’ survival.

Proposal to remove trade restrictions on Eswatini’s white rhinos:

REJECTED, 15 to 85; 26 Parties abstained

Mapping Next Steps for Rhinos

In addition to the two rhino-specific amendments, there was a move to adopt a document developed by the CITES Secretariat that maps out the status of Asian and African rhino conservation and trade, and puts forth steps that particular Parties must take to further the protection of these species.

During these discussions, IRF co-signed an intervention with World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and the Wildlife Justice Commission (WJC) highlighting a recent report that demonstrates the role of rhino horn trafficking as a transnational organized crime, and calling to reconvene the CITES Rhinoceros Enforcement Task Force. This task force, which was originally developed at CITES CoP 13, works “to improve international coordination and combat the growing trends in rhinoceros poaching and the associated illegal trade in rhinoceros horn.” Our intervention stated that reconvening the task force “should involve National enforcement agencies, including those tasked with addressing organized crime, from range, transit, consumer countries, and others with relevant experience, to bring a multi-disciplinary approach and enable successful prosecution of transnational wildlife criminals involved in the illegal trade of rhino horns.”

IRF is pleased to have been an official observer to the convention. We will keep track of Parties’ progress toward taking necessary actions to ensure the protection of rhinos through their national laws and enforcement. It is critical that Parties align their policies with decisions made at the COP, and develop resources and processes to report back on their progress. IRF will keep you updated as developments occur.