2023 State of the Rhino

Every September, the International Rhino Foundation (IRF) publishes our signature report, State of the Rhino, which documents current population estimates and trends, where available, as well as key challenges and conservation developments for the five surviving rhino species in Africa and Asia.

Download the 2023 State of the Rhino Report

Key takeaways from the 2023 State of the Rhino report:

- Poaching still threatens all five rhino species and has increased in several regions that had not previously been targeted.

- South Africa continues to battle devastating poaching losses of its white rhinos as poachers target Hluhluwe Imfolozi Game Reserve and other reserves within KwaZulu-Natal province.

- Black rhino populations are increasing despite constant poaching pressure.

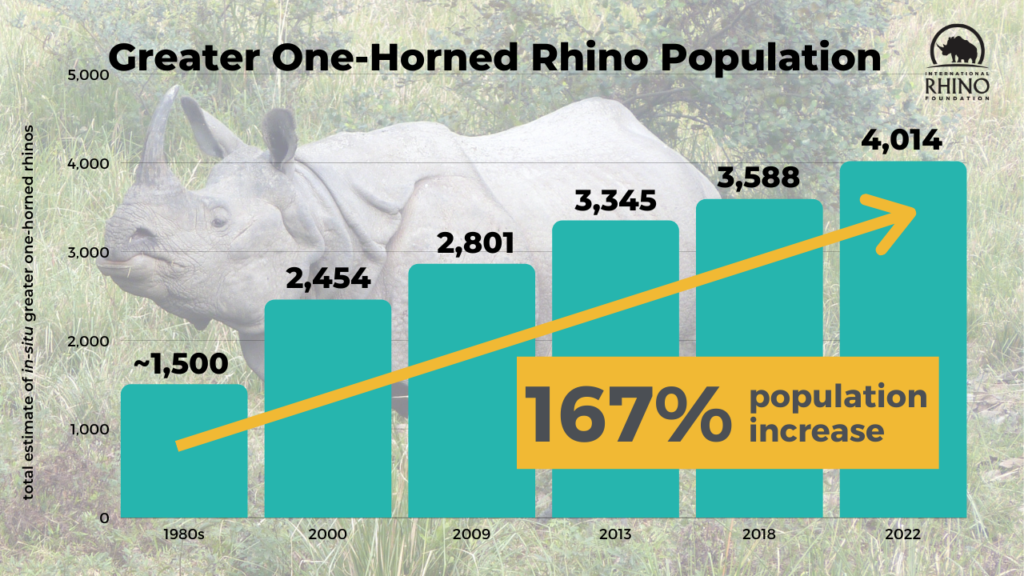

- The greater one-horned rhino population in India and Nepal continues to grow thanks to strong protection, wildlife crime law enforcement and habitat expansion.

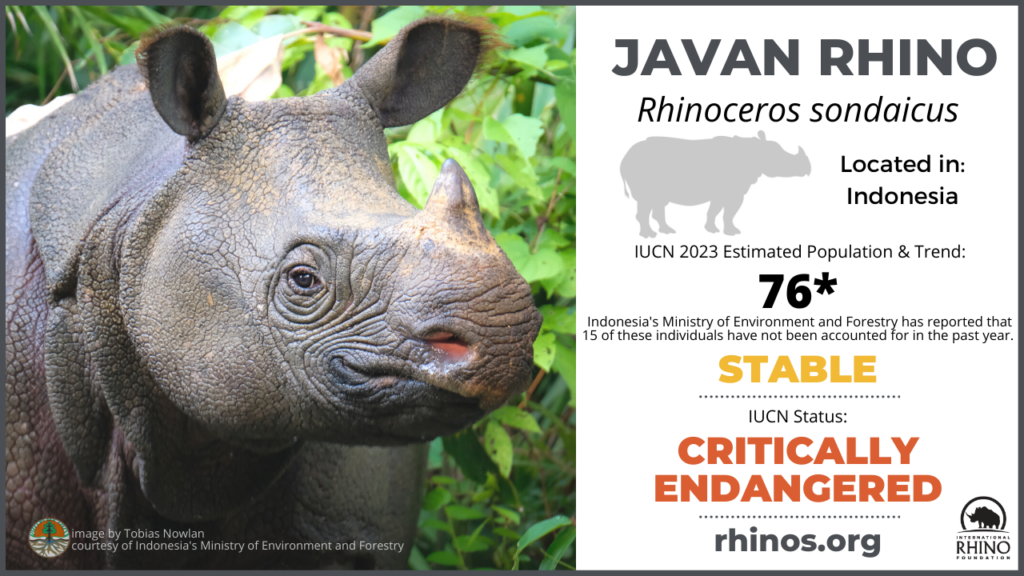

- The status and whereabouts of 12 of the approximately 76 remaining Javan rhinos is unknown.

- Signs of Sumatran rhinos are increasingly hard to find, creating more uncertainty about their population in the wild.

- 2,000 white rhinos from “World’s Largest Rhino Farm” will now be rewilded throughout Africa.

State of the Rhino

This World Rhino Day, September 22nd, 2023, news about the world’s five rhino species remains mixed. Two species, black rhinos and greater one-horned rhinos, continue to increase in numbers, while two species, white rhinos and Sumatran rhinos, have been experiencing declines (white rhino numbers were recently reported to have increased over the last two years, which is encouraging but not yet a long term trend). The remaining species, the Javan rhino, has an unknown population trend status.

The two most significant factors causing rhino populations to decline are poaching and habitat loss, but climate change is increasingly impacting many facets of rhino survival.

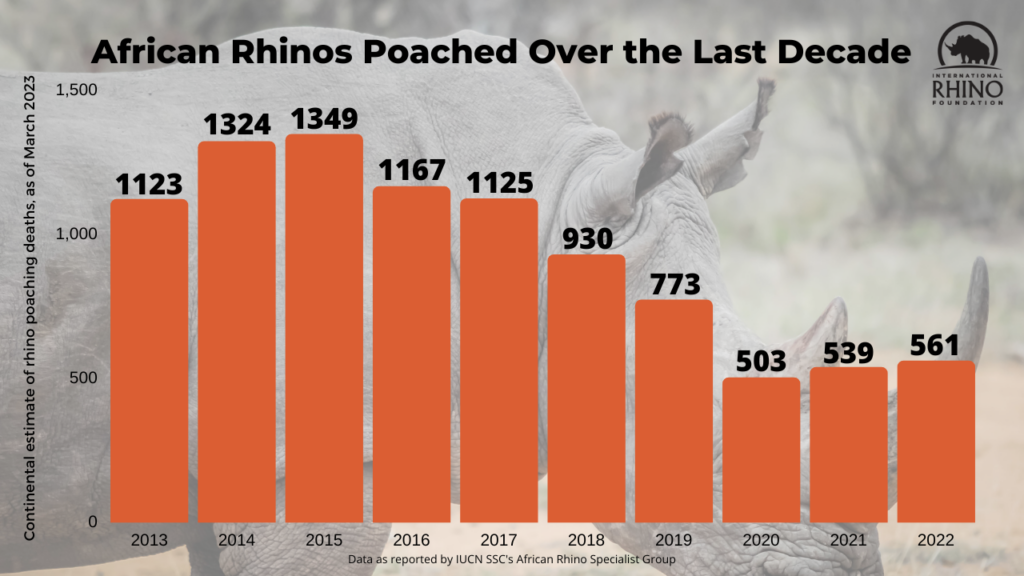

Poaching for rhino horn is the greatest threat to all five rhino species. Across the globe, rhino populations that were once considered less threatened have seemingly become the primary target of poaching efforts, which are orchestrated by highly organized, transnational criminal syndicates. After recording no poaching incidents last year, India suffered two poaching losses in 2023, one in Kaziranga National Park and one in Manas National Park. And Indonesia’s Ujung Kulon National Park, home to the world’s only population of Javan rhinos, has seen an alarming increase in incursion attempts over the past year. Indonesia’s Ministry of Environment and Forestry has reported a recently discovered unnatural Javan rhino death that is currently under investigation.

Across Africa, poaching patterns are changing. Over the last year, poachers have shifted their focus from the largest rhino populations to smaller, perhaps more susceptible ones. As poaching pressure increases around the continent, the number of white rhinos – the most populous of the five species – continues to decline. This can make it more difficult for poachers to find rhinos as big populations become less concentrated – spread out across large national parks and reserves. Large protected areas like Kruger National Park in South Africa have also greatly increased security measures to reduce the number of poaching incursions on their land. Poachers have reacted by targeting other, smaller areas, like province-run Hluhluwe Imfolozi Game Reserve, which has borne the brunt of South Africa’s rhino poaching deaths in the past year. Namibia, home to the largest number of black rhinos in the world, saw a devastating 93% increase in rhino poaching from 2021 to 2022.

Climate change poses an increasing risk to rhinos as well. The threats from climate change are broad and vary depending on the species. In Africa, climate change-induced drought is causing myriad detrimental impacts to human communities, which in turn can trigger a cascading effect for wildlife. Competition over water resources may also cause increasing strife and disruption between communities and between humans and wildlife, bringing people in ever closer contact with rhinos. Poverty resulting from loss of crops and livestock may lead to increased poaching as a way to earn income. Dry conditions could also cause an increase in wildfires, leading to a loss of habitat.

At the other end of climate disruption, dramatically increased precipitation and longer monsoon periods in Asia could cause more direct deaths of rhinos and humans alike. These seasonal floods are already causing some greater one-horned rhinos to get stranded on temporary islands or drown, and can cause calves to be separated from their mothers – these impacts would only worsen with intensified storms. Increased disease risk to humans and, potentially, rhinos could result from regular flooding conditions. Changing weather conditions and landscapes can also trigger an increase in invasive plant species, crowding out or overtaking native rhino food plants and causing general habitat degradation.

However, there are some bright spots. Greater one-horned rhinos continue to thrive due to strong protection and enforcement, and though the governments of India and Nepal did not conduct an official census this year, authorities believe the population is growing. And black rhinos in Africa are a cautious success story, rebounding in the past few decades at a strong growth rate despite still significant poaching losses. These two positive trends demonstrate what human will and capacity can do when governments are committed, conservationists are dedicated and communities are engaged and supportive. With the right interventions, all five rhino species can rebound and thrive in our ever changing world.

African Rhinos

White Rhino

IUCN Estimated Population and Trend: 16,803; Decreasing

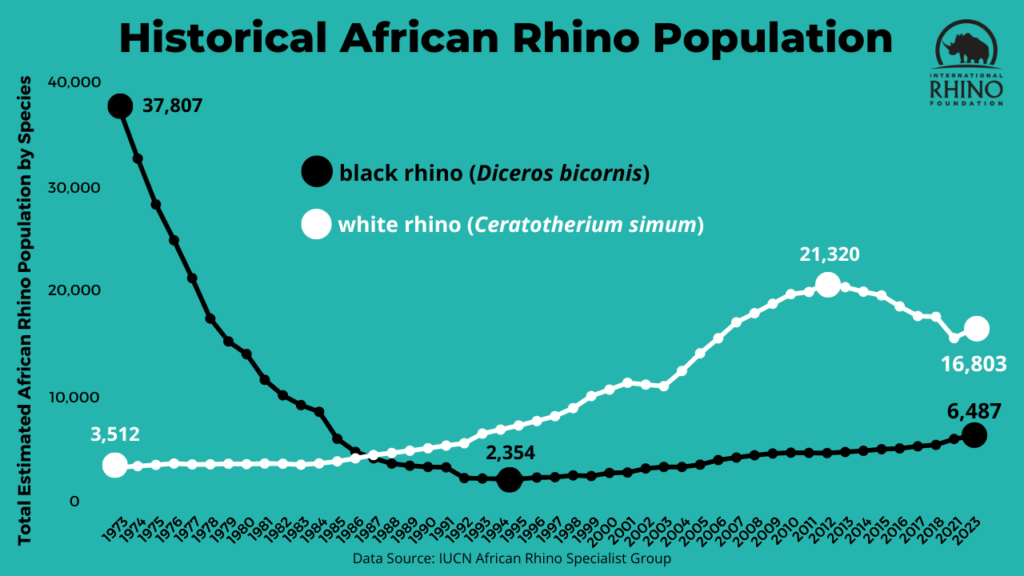

White rhinos (Ceratotherium simum) are the most populous of the five rhino species with approximately 16,803 animals across 11 countries in Africa. There are two white rhino subspecies, southern (C.s. simum) and northern (C.s. cottoni), but as there are only two northern white rhinos left in the world – both females – that subspecies is considered functionally extinct. Historically as a species, white rhinos made an incredible comeback from fewer than 100 individuals in the early 1900s to more than 21,000 at the end of 2012.

Unfortunately, from 2012 to 2021 their large numbers made them the primary target for rhino poachers, who are part of transnational criminal syndicates looking to sell rhino horn on the black market. During this period white rhino numbers decreased by 24% to an estimated 15,942. Although the number of rhino deaths has decreased since the most recent peak in 2015, poaching remains the biggest threat to rhinos, and white rhinos in particular have struggled to rebound. On September 21, 2023, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Species Survival Commission’s African Rhino Specialist Group (AfRSG) reported that there are now an estimated 16,803 white rhinos – the first increase for the species in over a decade.

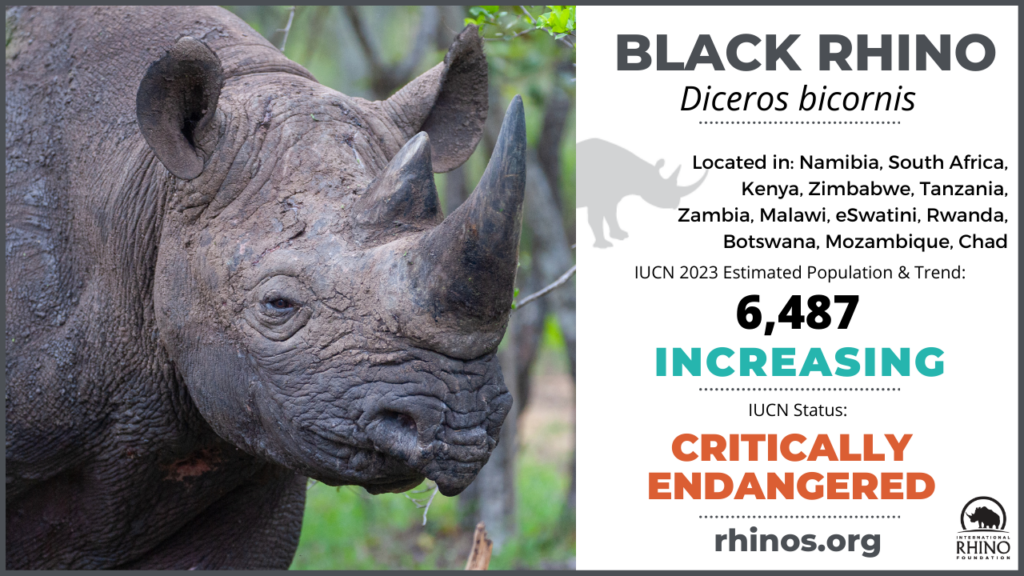

Black Rhino

IUCN Estimated Population and Trend: 6,487; Increasing

Black rhinos (Diceros bicornis) can currently be found in 12 countries in Africa, totalling an estimated 6,487 individuals.

At one time, black rhinos were the most common of the world’s rhino species and records indicate there could have been as many as 100,000 throughout Africa in 1960. By 1970, poaching had reduced the population to approximately 65,000 and black rhinos continued to decline precipitously until a low of about 2,300 individuals in the mid 1990s.

Thanks to intense protection and management efforts, black rhino populations stabilized and despite ongoing poaching pressure, and have increased by approximately 28% over the last decade.

Range Country Updates

Botswana

Rhino Population: ~265 ( ~23 black rhinos; ~242 white rhinos)

Poaching: Botswana reports 138 rhinos poached over last 5 years

2023 Rhino Headlines: At the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN’s) Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) Conference of the Parties in Panama in November, 2022, Botswana announced the country’s rhino population was greater than 300. However, with a reported 138 rhinos poached in the past five years (compared to only 2 reported poaching deaths from 2012 to 2017), there has been an alarming population decline. The increased poaching is thought to be triggered by criminal syndicates moving in from elsewhere in Africa as demand from Asian countries continues to drive the illegal horn trade.

Chad

Rhino Population: ~2 black rhinos

Poaching: None

2023 Rhino Headlines: Rhinos were translocated to Chad from South Africa in 2018 after a 50 year absence. Though just two rhinos currently survive in the country, we hope that officials will plan additional translocations when conditions are safe and appropriate.

Democratic Republic of Congo

Rhino Population: ~20 white rhinos

Poaching: Not Reported

2023 Rhino Headlines: This June, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) undertook a successful translocation of 16 southern white rhinos from &Beyond’s Phinda Private Game Reserve in South Africa into Garamba National Park in the DRC. Garamba, one of Africa’s oldest parks, had previously been home to northern white rhinos until the last individual was poached in 2006. This conservation initiative, undertaken by African Parks, Institut Congolais pour la Conservation de la Nature (ICCN) and &Beyond, was supported by the Barrick Gold Corporation, which also pledged ongoing funding for the next several years. Reintroductions such as this one – with government funder and other stakeholder support – are key to conserving rhinos into the future.

Eswatini

Rhino Population: ~146 (~48 black rhinos; ~98 white rhinos)

Poaching: None

2023 Rhino Headlines:

The small country of Eswatini, formerly Swaziland, continues to do a remarkable job protecting their rhinos from poaching. This is especially impressive considering their close proximity to Kruger National Park and other areas in South Africa which have been heavily hit by poaching in recent years. While those dedicated to rhino conservation, primarily Big Game Parks, which manages the country’s rhino population under an agreement with the government, have had tremendous success, it comes at a price – the toll it takes on rangers and their families. Rangers in Eswatini put their lives at risk daily to protect the remaining rhinos from poaching.

Kenya

Rhino Population: ~1811 (~938 black rhinos; ~873 white rhinos)

Poaching: 0 in 2022

2023 Rhino Headlines: Kenya is the stronghold of the Critically Endangered eastern black rhino (D.b. michaeli), housing approximately 75% of the world’s population. The major goal of Kenya’s black rhino conservation plan is to increase overall rhino numbers at a minimum of 5% annually to minimize the loss of genetic diversity and to provide a buffer against potential poaching losses. Kenya reported a zero poaching rate in 2022 and no poaching deaths to date in 2023 – a significant achievement.

Twice this year, once in February and again in May, researchers from multiple institutions collaborating under the partnership known as BioRescue Consortium, collected eggs from Fatu, one of two remaining northern white rhinos in the world. Fatu, who lives with her mother Najin at Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya, is critical to the future of this subspecies, as are the assisted reproductive technologies (ART) being employed to try to bring it back from the brink of extinction. ART processes are complicated and delicate procedures. After the northern white rhino eggs are harvested, they are shipped to Avantea lab in Italy, where scientists are carefully working to create embryos for future transplant into a suitable southern white rhino surrogate, hoping for an eventual live birth of a northern white rhino. The two egg collections this year resulted in a total of seven embryos, a promising number.

Malawi

Rhino Population: ~56 black rhinos

Poaching: Not Reported

2023 Rhino Headlines: Rhinos disappeared from Malawi by the 1980s, but thanks to several successful reintroductions into Liwonde National Park and Majete Wildlife Reserve, black rhinos are reportedly doing well in Malawi.

Mozambique

Rhino Population: ~16 ( ~14 white rhinos; ~2 black rhinos)

Poaching: Not Reported

2023 Rhino Headlines: After 2022’s translocation of white rhinos into Zinave National Park, most of the reintroduced animals have survived and are doing well.

Namibia

Rhino Population: ~3,612 ; increasing

(~2,196 black rhinos; ~1,416 white rhinos)

Poaching: 87 in 2022

2023 Rhino Headlines: After last year’s devastating poaching losses in Namibia, with a record high of 87 rhinos killed, Namibia took swift and decisive action this year, dehorning hundreds of rhinos, expanding the Rhino Ranger community program and initiating a ranger horse unit for Etosha National Park, home to the world’s largest black rhino population. These combined efforts are proving effective in slowing the tide of illegal activity.

Rwanda

Rhino Population: ~58; increasing (~28 black rhinos; ~30 white rhinos)

Poaching: None Since Their Reintroduction

2023 Rhino Headlines: After a ten year absence, rhinos were reintroduced to Rwanda in 2017. The most recent translocation occurred in 2021, when 30 white rhinos were moved into Akagera National Park. Rwanda’s rhino population, found only in Akagera, is doing well. Thanks to several births this year, the populations of both black and white rhinos are increasing and there have been no rhinos lost to poaching since their reintroduction.

South Africa

Rhino Population: ~15,024 ( ~2,056 black rhinos; ~12,968 white rhinos)

Poaching: 448 in 2022; 231 in first 6 months of 2023

2023 Rhino Headlines:

The biggest news from South Africa this year is the sale of Platinum Rhino Project and their 2,000 southern white rhinos to nonprofit African Parks, which will begin historic and critical translocations across Africa in order to build rhino populations in key protected areas. After years of uncertainty about the fate of these animals, which comprise an eighth of the world’s white rhino population, this plan is a welcome relief and will greatly contribute to conservation of the species.

South Africa continues to battle devastating poaching losses. Although there has been a decline in poaching in Kruger National Park and in the country overall in 2023, poachers have shifted their focus to coastal KwaZulu-Natal province, particularly embattled Hluhluwe Imfolozi Game Reserve. The reduction in poaching in Kruger is likely due in part to increased security measures and in part due to the declining rhino population, making targets harder to find for poachers.

Tanzania

Rhino Population: ~212 black rhinos

Poaching: Not Reported

2023 Rhino Headlines: In June of this year, Tanzania launched the National Anti-Poaching and Wildlife Management Area Strategies, a program to combat poaching and illegal wildlife trade. Led by the Ministry of National Resources and Tourism, with support from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Global Environment Facility, the project focuses on “enhancing the financial and technical capacities of relevant authorities, fostering collaboration among stakeholders, and mobilizing local communities residing near protected areas.” With no poaching of any species, including rhinos, recorded in the past year, Tanzania is already having success. The number of rhinos recorded in 2022 has already surpassed the target set in the National Rhino Conservation Strategy – a goal of 205 rhinos by December 2023.

Uganda

Rhino Population: ~35 white rhinos

Poaching: None Reported

2023 Rhino Headlines: In February of this year, Uganda announced that wildlife populations in the country, including white rhinos, are increasing after years of decline. Officials hope to conduct additional reintroductions into protected areas in upcoming years.

Zambia

Rhino Population: ~66 ( ~58 black rhinos; ~8 white rhinos)

Poaching: None Reported

2023 Rhino Headlines: Zambia’s reintroduced rhino population in North Luangwa National Park continues to do well this year, and is being considered as a source population for additional rhino translocation efforts elsewhere. The Zambian government’s successful arrests this year of several notorious poachers, and their convictions and lengthy jail sentences, will hopefully serve as a deterrent.

Zimbabwe

Rhino Population: ~1,033 ( ~616 black rhinos; ~417 white rhinos)

Poaching: 13 in 2022

2023 Rhino Headlines: Last year, Zimbabwe’s rhino population surpassed 1,000 for the first time in three decades, with 90% of the country’s rhinos living in the Lowveld region, where formerly degraded farmland was converted to wildlife management areas. From monitoring and security support to treating, rehabilitating and translocating rhinos, there is an immense amount of work that goes into helping rhinos thrive in the wild in Zimbabwe. Encouragingly that hard work is paying off – there were no rhino poaching deaths reported in Zimbabwe’s Lowveld during the first half of 2023.

Asian Rhinos

Greater One-horned Rhino

IUCN Estimated Population and Trend: 4,014; Increasing

Greater one-horned rhinos (Rhinoceros unicornis) reside primarily in India and Nepal, though there is a population that occasionally crosses into Bhutan. Bhutan, India and Nepal work together to implement a trans-boundary management strategy for the greater one-horned rhino. Thanks to this collaboration and strict government protection and management, the greater one-horned rhino population has steadily increased over the last century, and has grown about 20% over the last decade.

Though the greater one-horned rhino population is growing, the species is still classified as Vulnerable. Poaching remains a significant threat, and the species has been driven from many of the areas where it used to be common. Its full recovery depends not only on protecting rhinos where they have managed to survive, but also reintroducing them to places from which they’ve disappeared. Another significant landscape-level threat to greater one-horned rhinos is the prevalence of invasive species, which choke out native rhino food plants and limit the amount of habitat available.

Range Country Updates

India

Rhino Population: ~3,262 greater one-horned rhinos

Poaching: In 2022, one rhino had its horn removed but was left alive. There have been two poaching deaths to date in 2023.

2023 Rhino Headlines: Rhino translocations to Manas National Park set for the beginning of 2023 were rescheduled for 2024 while security measures are reinforced after a poached rhino was discovered in January.

In the past year, the Assam government finalized the addition of approximately 200 sq km to Orang National Park in north-central Assam, more than doubling the size of this protected area and key rhino habitat. This proactive step will create additional space for Assam’s growing rhino population and help ensure the species’ long-term growth and security by allowing rhinos to move freely between these protected areas. With this added land, Orang National Park is now connected to Burhachapori Wildlife Sanctuary in the east, completing the creation of a linked corridor between all the protected areas in Assam that hold (or are planned to hold) rhinos: Manas National Park, Pobitora Wildlife Sanctuary, Orang National Park, the Laokhowa and Burhachapori Wildlife Sanctuaries and Kaziranga National Park.

Nepal

Rhino Population: ~752 greater one-horned rhinos

Poaching: None reported in 2022, 2 rhinos poached in Chitwan in January 2023

2023 Rhino Headlines: In an increasingly uncommon event for Nepal, two rhinos were poached this January in Chitwan National Park. Fifteen suspected poachers were arrested in February and there is an investigation underway.

Nepal hosted the 3rd Asian Rhino Range States Meeting in Chitwan National Park in February. Government authorities from Bhutan, India, Nepal, Malaysia and Indonesia, as well as IUCN SSC Asian Rhino Specialist Group Members and several rhino nonprofits, gathered to review the current efforts on Asian rhinoceros conservation and to discuss future priorities. The resulting declaration on rhino conservation is awaiting final signatures from government officials.

Bhutan

Rhino Population: No permanent population

Poaching: 0

2023 Rhino Headlines: Manas National Park straddles the border between India and the Kingdom of Bhutan. Rhinos are known to cross the border and are included in the population figures for India, but Bhutan collaborates closely with India on transboundary management and officials there hope to eventually establish a Bhutanese population.

Javan Rhino

IUCN Estimated Population and Trend: 76 (with 12 missing); Stable

Since the 2011 death of the last Javan rhino (Rhinoceros sondaicus) in Vietnam, the species now only exists in one country, in one national park – Indonesia’s Ujung Kulon National Park (UKNP). Once ranging throughout southeast Asia, Javan rhinos have been hunted to near extinction with a single, small population remaining. UKNP has conducted intensive Javan rhino population monitoring since 1967, when the Park estimated that just 25 individuals remained. Since then, the population has been slowly increasing to an estimated high of 76 rhinos in 2022. Unfortunately, earlier this year Indonesia’s Ministry of Environment and Forestry noted that 15 of these 76 individuals have not been identified on camera traps for the last three years (recently, three of these individuals have been accounted for). It is not known whether these rhinos have simply avoided detection by camera traps, passed away naturally or been poached. Within the last year, UKNP has found evidence of attempted poaching incursions and has responded by closing the Park to visitors, increasing protection and monitoring efforts and implementing added security systems. In addition to the constant threat of poaching shared by all rhino species, the Javan rhino population in Ujung Kulon faces several unique threats. These include an unbalanced sex ratio of about two males for every one female, a lack of genetic diversity within the existing population, and only having access to a single habitat which has neared its carrying capacity for rhinos and is located in an area prone to natural disasters.

Sumatran Rhino

IUCN Estimated Population and Trend: 34-47; Decreasing

Sumatran rhinos (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) are also extant in just one country, Indonesia. The IUCN SSC Asian Rhino Specialist Group (AsRSG) reports that there are up to 4 isolated populations and as many as 10 subpopulations of Sumatran rhino left in Indonesia. Only one of these wild populations, in Gunung Lesuer, is believed to have enough individuals to be viable. Uncertainty is and has been the key word for tracking Sumatran rhino population trends over time. As this reclusive species seems to disappear further into dense jungles, direct sightings have become rare and indirect signs like footprints are getting harder to find. The government of Indonesia reports that there are no more than 80 Sumatran rhinos in total, while the AsRSG specifies that the actual count could be as low as 34-47 individuals with no single subpopulation having more than 30 rhinos. There has been no evidence of Sumatran rhino poaching found for over a decade – there also have been no naturally occurring carcasses discovered either, making the species’ disappearance even more of a mystery. The beacon of hope for the species is the breeding program at the Sumatran Rhino Sanctuary, a protected, semi-wild facility in Sumatra that has produced three calves and continues its breeding efforts to create an insurance population of rhinos.

Range Country Updates

Indonesia

Rhino Population: ~110 – 123 (76 Javan rhinos, 34-47 Sumatran rhinos)

Poaching: 1 suspected Javan rhino poaching

2023 Rhino Headlines: Increased illegal incursions into Ujung Kulon National Park, with a recent suspected poaching incident, is putting the precarious Javan rhino population at even greater risk. The Government of Indonesia is coordinating a strong response, pledging to take firm action against the perpetrators.

The Sumatran rhino born in 2022 turned one year old in March, marking a remarkable milestone in the Sumatran rhino conservation breeding program, and a ray of hope for the future.

For more than 32 years, the International Rhino Foundation has managed, facilitated and funded conservation initiatives for some of the most threatened rhino populations throughout Africa and Asia. Over the decades, tactics to keep rhinos safe and see them thriving may change, but the strategies do not. As long as there is demand for rhino horn, poaching will remain a threat. With the global human population at more than 8 billion and growing, rhinos and other wildlife will continue to compete for space and resources – which will only be further exacerbated by climate change impacts. To mitigate these threats to rhino species, their populations must become more resilient. Keeping poaching and other deaths as low as possible while bolstering birth rates and genetic diversity of each species are the seemingly simple solutions to building this resilience and seeing rhinos thrive in the wild. In practice, each species has its own unique set of conservation challenges to overcome, but with just over 27,000 rhinos left, it is clear that all rhino holders need to collaborate and manage these species as transnational metapopulations – regardless of borders.

IRF is committed to resourcefully and innovatively applying expertise and funds towards long-term tactical investments to conserve rhinos. We partner with individuals, organizations and government agencies to foster solutions in the best interest of the world’s rhinos based on science, political realities and available resources. Our work prioritizes the following broad strategies to ensure the survival of rhinos:

- Protection: Protect rhinos from poaching through a comprehensive, multi-layered approach that includes funding, technology, skills training and ranger support, as well as collaboration with law enforcement agencies and community stakeholders.

- Population Management: Increase and maintain healthy rhino populations at levels that can be sustained within each ecosystem in adequately secure areas of their historic range.

- Habitat Management: Secure, expand and restore the habitats that rhinos depend on to ensure the long-term survival of all five rhino species.

- Connecting People for Conservation Action: Unite and engage diverse audiences in meaningful conservation actions to protect rhinos and their habitats.

- Community Development: Partner with communities to create conservation awareness and sustainable natural resource management programs that ensure those who live alongside rhinos benefit from and support rhino conservation efforts.

- Capacity Building: Support, expand and share technical capacity to achieve locally-led, sustainable rhino conservation in Africa and Asia.

- Demand Reduction: Explore and support innovative techniques to reduce the demand for rhino horn and to maximize penalties for its illegal possession and use.

- Advocacy: Encourage and support government action for rhino conservation by helping to guide local, national, regional and international conservation policies and plans.

- Trafficking Disruption: Actively disrupt wildlife trafficking networks by supporting research and analysis, intelligence gathering, investigations and wildlife crime prosecutions.

This report was prepared by the International Rhino Foundation from sources including the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora African and Asian Rhinoceroses – Status, Conservation and Trade report (August, 2022), the African Rhino Specialist Group, the Asian Rhino Specialist Group, TRAFFIC, African Parks and input from IRF’s international advisors and partners.

State of the Rhino 2023 has been updated since its original publication on September 18, 2023 to reflect the reported changes in black and white rhino population numbers.