Portrait of a Rhino Poacher, Part IV

As the International Rhino Foundation re-launches Operation: STOP POACHING NOW, we have carefully considered how to tell the story of the unspeakable fate met daily by poached rhinos. While we don’t usually show graphic content, we believe that you as our supporter deserve to see, once in a while, what and whom we’re up against. We’ve invited our colleague Mick Reilly, Head of Conservation and Security from Big Game Parks in the Kingdom of Swaziland, to share his first-hand experience with the poaching crisis as part of an in-depth article in multiple parts to be published on the IRF blog. Here is Swaziland’s story.

As the International Rhino Foundation re-launches Operation: STOP POACHING NOW, we have carefully considered how to tell the story of the unspeakable fate met daily by poached rhinos. While we don’t usually show graphic content, we believe that you as our supporter deserve to see, once in a while, what and whom we’re up against. We’ve invited our colleague Mick Reilly, Head of Conservation and Security from Big Game Parks in the Kingdom of Swaziland, to share his first-hand experience with the poaching crisis as part of an in-depth article in multiple parts to be published on the IRF blog. Here is Swaziland’s story.

**Please note that this newsletter includes graphic photos and descriptions that sensitive readers may find disturbing.

Written by: Mick Reilly

Head of Conservation and Security

Big Game Parks, Swaziland

July 2014

FEBRUARY 2014 – UPDATE

Mozambique and Vietnam

Swaziland is a small, land-locked country with two neighbors: Mozambique and South Africa. With the absence of any meaningful law enforcement effort by the Mozambican government to control her citizens plundering her neighbors’ National assets, and the absence of laws to appropriately deal with poaching and wildlife trafficking (along with the high incidence of corruption), many of the Vietnamese syndicates have relocated from South Africa to Maputo and other Mozambican centers, where their rhino horn trafficking operations from Africa to the Far East are conducted with virtual impunity and little or no risk. The apparent viral crime epidemic which is underway in Mozambique, where rhino poachers and horn traffickers are looked up to as popular role models by their communities, demonstrates that simple lifestyle audits and law enforcement is not in place. A reciprocal high incidence of corruption and lack of political will towards law enforcement in Vietnam regarding the control of the illegal rhino horn trade makes the positioning of the syndicates in Mozambique ideal for their booming illegal global trade.

Had Swaziland not had deterrent laws and a non-tolerant attitude towards rhino poaching, the Vietnamese syndicates might just as easily have established themselves in Swaziland, and Swaziland would most likely have been in the same embarrassing position that its neighbors now face, with international poaching and smuggling of her national assets laundered through Mozambique. It is no coincidence that Mozambique is the only country with the dubious distinction of having had her rhino population go extinct (for the third time) in 2012, while Vietnam’s Javan rhino went extinct in 2010.

In response to the exploding rhino poaching crisis in South Africa and the curtailment by the Mozambican government of the ability of the KNPs’ rangers to follow poachers in hot pursuit into Mozambique some years back, retired member of the South African National Defence Force, Major-General Johan Jooste, was assigned to direct anti-poaching operations in the KNP which supports the world’s largest rhino population. This curtailment of “hot pursuit” raises the question of the seriousness of political will and how important rhino poaching control is really considered to be. South Africa, in attempting to bring rampant poaching under control, has, among other measures, legislated norms and standards to introduce more regulations to regulate the capture, hunting and possession of rhinos and their products, and has developed Memoranda of Understandings with Vietnam and Mozambique, the allocation of rhino crimes to the agenda of national and provincial joint committees and declare rhino crimes a priority crime. All of this has positively elevated the profile of rhino poaching in the courts. Of concern, however, given the contribution of the private sector to rhino conservation, is the potential for bureaucracy and red tape created by over-regulation. Over-regulation is a serious inducement to disinvest in rhinos. Generally, the private sector’s reaction to over-regulation is simply to reinvest resources into less beaurocratic ventures such as livestock or monocultures; this then results in the loss of rhino habitat. Even so, in South Africa, this appears to be a case of “too little, too late”. Swaziland’s strategic emphasis should be firmly grounded in preventing the development of a similar situation.

As you read this, the military campaign against mainly Mozambican armed insurgents has turned the KNP into a virtual war zone. This has increased law enforcement pressure on the poaching syndicates significantly and caused their operatives to spread deeper into South Africa to the west of KNP and to Kwa-Zulu Natal in their search for “softer” targets. It is only a matter of time before Swaziland becomes an alternative target for Mozambique-based poachers because of its proximity to Maputo. How much longer Swaziland can hold out against these mounting odds, only time will tell.

International Intervention and Terrorism

In January 2014, the United Nations Security Council officially acknowledged that illegal wildlife trade is being used to finance international terrorism, particularly in Central and East Africa through terrorist organizations such as Al Shabaab. Consequently, two resolutions that attempt to address this crisis were passed.

Indicatively, at the CITES (United Nations Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) Conference of the Parties in 2013, Mozambique and Vietnam both were listed among countries that require special international attention regarding complicity in the global rhino poaching and horn trafficking crisis. As things stand now, it is hardly in Mozambique’s financial interests to control this illegal trade, which has become a significant economic base for some of its citizens. These people are reaping the vast profits from South Africa’s national assets at minimal cost, while South Africa carries all the costs of rhino management and protection.

The illegal cross-border incursions by Mozambicans, armed with illegal weapons, into neighboring countries with the sole purpose of destroying that neighbors’ economic assets for self-enrichment — and in the process endangering the lives of tourists and those responsible for guarding those assets — is increasingly being regarded as an act of terrorism. Only relentless and determined international political and economic pressure is likely to move the Mozambican government into addressing the threat that their citizens are to their neighbors’ national assets, as they have so far been unable to do this for their own wildlife assets.

Exponential Poaching Escalation

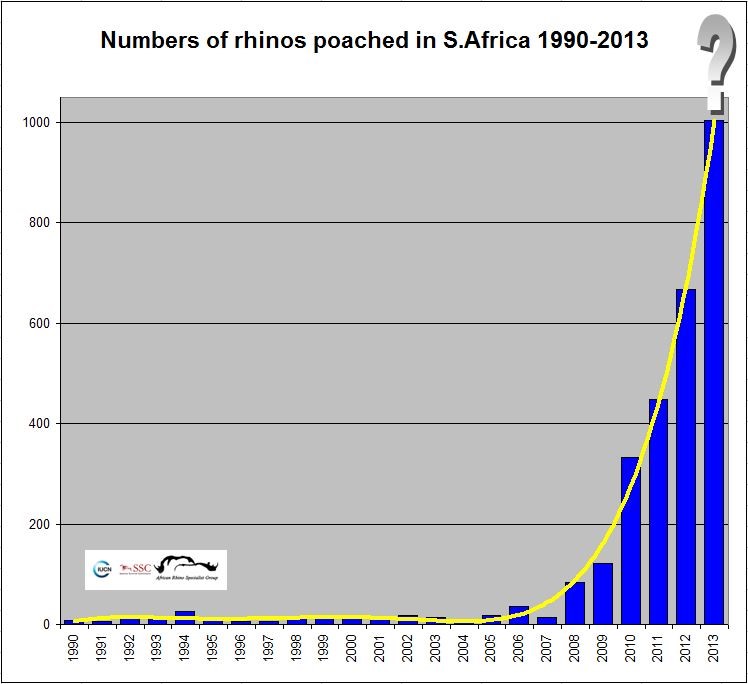

Below is a graph produced by the IUCN African Rhino Specialist Group showing the exponential increase in the rate of poaching since 1990. Since 2007, despite international intervention and in the face of a sharply rising human and rhino body count, the number of poached rhinos in South Africa has continued to escalate at an average annual rate of approximately 148.5% over the past 6 years.

If the rhino poaching situation was considered serious in 2011, then the 2014 situation should serve as a major wake-up call to all of those who may have underestimated the capacity of the criminal syndicates to infiltrate rhino conservation organizations and the threat this poses in relation to the possible extinction of African rhinos.

Importantly, the released figures reflect only the South African rhinos that are found and reported as having been poached and do not include rhinos from other countries — the rhinos that are poached and never found, orphaned calves whose mothers are poached and die as a result of hunger and stress or predation, and the calves that die in-utero. Further, the official figure is likely to be significantly less than the true number of rhinos that actually die as a result of poaching since those figures are based only on carcasses found.

When one considers the rhino mortalities that are not included in the official figure, and that with only 25,509 rhinos of both species remaining in Africa (African Rhino Specialist Group, 2014), rhinos are now being poached faster than they are being born, and our generation is seriously facing the very real prospect of the imminent extinction of both species of African rhinos in the wild.

Since the two rhinos were poached allegedly by the Songimvelo syndicate at Hlane RNP in June 2011, at least 2,403 rhinos have been poached in South Africa alone (as of February 9, 2014), an increase of 714%, while the suspects are out on bail and still have not stood trial for the poaching of the Hlane rhinos. Had these suspects been subject to the provisions of Swaziland’s Non-Bailable Offences Act, which was sadly repealed in 2005, their trial would most likely have been completed by now and justice seen to have been done. Instead, the longer they remain in our communities without going to trial, the more likely they are to return to poaching and other serious crimes as they believe that they have got away with their crimes. Additionally, the two suspects who remain on the Interpol I 24/7 Red Notice still have not been extradited from South Africa to Swaziland for trial — and they are known to be continuing their illegal business.

“Hunger and poverty”

As with the drug trade, poaching syndicates continue to unashamedly exploit the weak economic status and the local knowledge held by members of communities and employees of game reserves by luring and recruiting them into becoming poaching “mules.” The former rangers-turned-poachers, who both left gainful employment to facilitate and participate in the poaching of rhinos at Hlane in 2011, are clear examples. It is no secret that local bush meat poachers quickly graduate to syndicated poaching due to their superior local knowledge and bush craft skills. It is also no secret that once groups of poachers (or any other criminals) gain experience and confidence, the groups tend to expand and form subgroups, drawing in new participants and proliferating the crime base. This situation is accentuated if law enforcement efforts are tolerant or weak and ineffectual and if reward outstrips risk (particularly in the courtrooms). If “crime pays,” the inevitable growth of crime will occur with an associated increase in aggression, as well as the use of military and other deadly weapons. This is exactly what has been allowed to happen in South Africa, Mozambique and Vietnam. It should NOT be encouraged to happen in Swaziland. Conservation simply cannot compete with such promises of wealth by syndicates who criminalise and put otherwise law-abiding people at risk. Accordingly, a zero-tolerance approach to all poaching needs to be vigorously enforced.

“Hunger and poverty” are no more an excuse to justify poaching than it is for burglary and violent robbery or an abused upbringing is to justify rape. They are all crimes which are perpetrated with planning and intent.

Poaching crimes are undoubtedly motivated by the promise of quick wealth and harbor all the characteristics of syndicated organized crime. They heavily impact sovereignty and incite hostile attacks on a country’s natural and cultural heritage, reducing sustainability and the well-being and ability of their victims to practice the wise utilization of natural resources. Rhino poaching is, in fact, an act of terrorism. It is driven by hostile foreign criminals who are destroying and stealing Africa’s unique financial assets, and should be declared a National Disaster in countries where such poaching takes root.

Now is the time, more than ever before, that people across the globe — from the rangers on the ground to Parliaments and the highest Courts — should fully embrace their responsibilities and cooperate to counter this unfolding global disaster to prevent the extinction of rhinos and the resultant national impoverishment and international embarrassment.

“Only after the last tree has been cut down,

Only after the last river has been poisoned

Only after the last fish has been caught

Only then will you realize that money cannot be eaten”

(Cree Indian Prophecy)

…and the same applies to the world’s rhinos!

Let us remember the words of King Sobhuza II, who reigned as Swaziland’s King for 61 years. As he looked out over a waterhole teeming with wildlife at Hlane RNP, he said: “Our children will never forgive us if we allow all this to disappear.”

Mick Reilly

Head of Conservation and Security

Big Game Parks, Swaziland

July 2014

You can help bring these criminals to justice by supporting Operation: STOP POACHING NOW. Every gift, large or small, helps. Every gift allows us to do more.