The Curse of the Unicorn – #NationalUnicornDay

In his book, The Future of Life, biologist Edward O. Wilson had this to say about the first time he laid eyes upon the rare Sumatran rhinoceros in the flesh: “One of the most memorable events of my life occurred on a late May evening in 1994, in a back room of the Cincinnati Zoo, when I walked up to a four-year-old Sumatran rhinoceros named Emi, gazed into her lugubrious face for a while, and placed the flat of my hand against her hairy flank. She made no response except maybe to blink her eyes. That’s it; that’s all that happened. No matter: I had at last met my real-life unicorn.”

The unicorn is an imaginary creature that symbolizes purity. It was first described by Ancient Greek naturalists as a species that inhabited the distant land of India. Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD) spoke of the monoceros, “a very fierce animal … which has the head of the stag, the feet of the elephant, and the tail of the boar, while the rest of the body is like that of the horse; it makes a deep lowing noise, and has a single black horn, which projects from the middle of its forehead, two cubits in length.” Perhaps the Indian rhinoceros comes to mind?

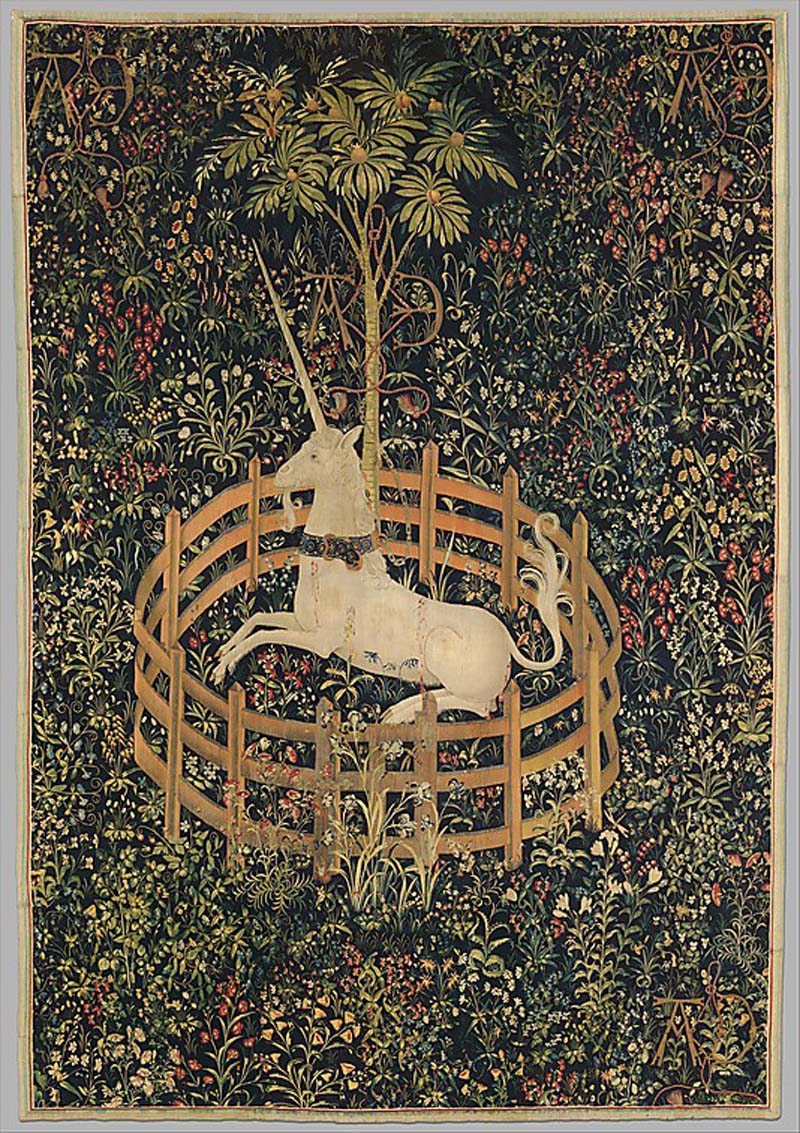

The unicorn legend became popular throughout Europe during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The creature was said to roam the woodlands and could only be captured by a virgin. Many people believed that its horn, which was called an alicorn, was an antidote to poison and could be used to treat illness. Alicorns could be purchased from Scandinavian traders, but the price was extravagant – per weight, supposedly many times more than that of gold. The average alicorn was grooved and about three feet long. Unfortunately, it never came from a unicorn. A Dutch physician and naturalist, Ole Wurm, told the world the truth, the alicorn was really the long tusk of the small arctic whale known as the narwhal. Narwhals are still hunted today for their tusks by certain indigenous populations, but many experts believe that this is not sustainable over the long-term.

That the rhinoceros might be likened to the legendary unicorn is not so far-fetched, certainly no stranger than ancient sailors believing that hefty, whiskered sea mammals like dugongs and manatees were really mermaids. Rhinos are distant relatives of horses and the horns of some rhino species can grow quite long. So, with a dash of imagination and perhaps a pinch of intoxication, a person viewing a rhino could conjure the image of a unicorn in his mind, although that transformation would seem to be a bit easier with several of the antelope species, such as the oryx, that sport spectacular horns, albeit in pairs and from the top of the skull instead of the nose.

Like the unicorn’s unusual appendage, the rhino’s horn also was once believed to detect and neutralize poison, and it is still believed by many Asian people to have medicinal properties. As a result, white and black rhinos in southern Africa are now being killed by poachers at the rate of almost two per day. If such slaughter continues, decades of dedicated efforts to bring these species back from the brink of extinction will have been for naught.

Unicorns never existed, but rhinos can and must survive as living legends.

If you’d like to know more about what the International Rhino Foundation is doing to combat poaching in southern Africa, visit our website.

3 thoughts on “The Curse of the Unicorn – #NationalUnicornDay”

Reblogged this on Natanedan's Blog.

Sumatran rhinoceros is an animal rights should be protected.

The discovery of a single-horned deer in an Italian preserve resurrects humankind’s fascination with the unicorn.