Nina’s Travel Blog: The Last of a Subspecies

I was beyond excited to meet Fatu and Najin. After two years as executive director of the International Rhino Foundation (IRF), I had heard as much about the last two northern white rhinos (Ceratotherium simum cottoni) as any other animals in my career. As the last two of a subspecies, Fatu and Najin are famous, representing so many things: the fragility of small populations, the loss of biodiversity broadly, the damaging structural and economic forces that cause rhino poaching and wildlife trafficking, and humanity’s basic failure to recognize and protect things that matter.

Devastatingly, the last two northern white rhinos are both female – mother (Najin) and daughter (Fatu). This has obvious and frightening implications for the future of the subspecies, testing science in a race against time as reproductive biologists around the world work to create a first of its kind “artificially reproduced” northern white rhino, no simple undertaking (we’ll discuss the assisted reproductive technology, or ART, being used for northern white rhinos in a future blog). I felt it was important to visit Fatu and Nanjin to better understand how IRF can best talk about and support northern white rhino conservation efforts.

My excitement mounted as Maggie Moore, IRF’s Deputy Director, and I arrived in Kenya, where Fatu and Najin are housed at Ol Pejeta conservancy in Laikipia County, in the central part of the country. After several hours of challenges flying from Nairobi to Nanyuki airport near Ol Pejeta, thanks to an unexpected presidential parade that shut down airspace, we finally arrived.

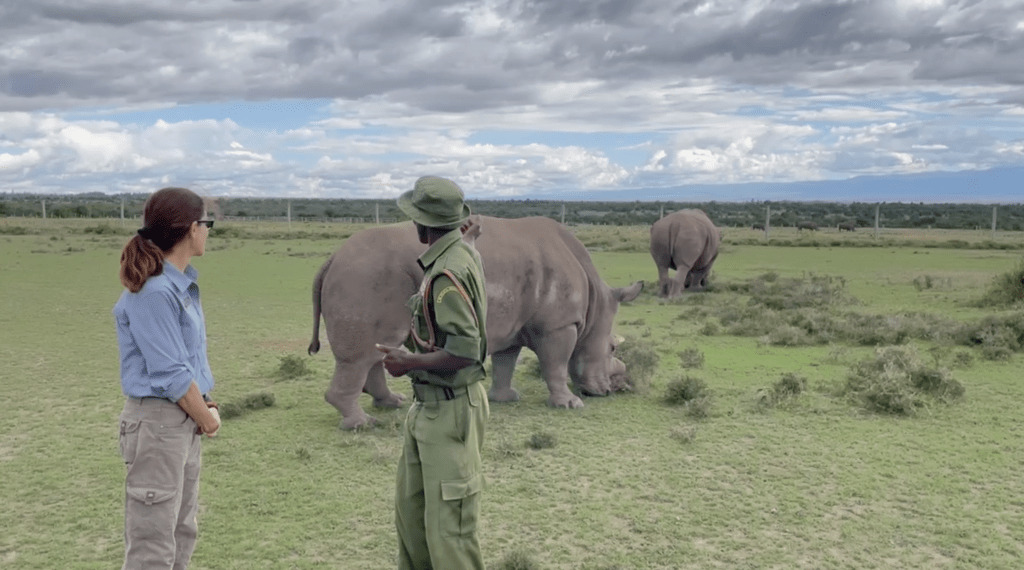

We were met by Samuel Mutisya, the head of conservation at Ol Pejeta (or “Ol Pej,” as those who know it well call it). Samuel has long run successful conservation programs at Ol Pej, including that for the northern white rhino. He generously spent time chatting with us about all of Ol Pejeta’s wildlife and habitat conservation efforts, and took us out to meet Fatu and Najin.

As we drove out to meet “the ladies,” I saw three white rhinos grazing peacefully in the open range. “Oh, they have southern whites too”, I thought to myself – the other subspecies of white rhino (Ceratotherium simum simum). Then we pulled up and I realized it was Fatu and Najin, along with a southern white “friend” for company. I couldn’t believe they were grazing so peacefully on the grassland, oblivious to their fame or imperiled status in the world. I felt like I wanted them behind bullet proof glass or wrapped in bubble wrap for their own protection, but was glad to see them living like any other rhinos.

And of course they are strongly protected. Prior to meeting these two, Samuel had taken us to meet and talk to the large team of rangers, including a well trained team of K-9 rangers, who reside right next to where Fatu and Najin range. We also saw the impressive technology used to keep a close eye on the entire conservancy, and the rhinos in particular. Ol Pejeta, and Kenya in general, have been very successful at reducing poaching. Kenya lost only 6 rhinos to poachers in 2021, and its rhino population grew by nearly 10%.

For me, meeting Fatu and Najin was better than meeting any Hollywood actor or famous musician. I was surprised at how emotional I felt – these glorious creatures are the last two of their kind in the world. A large, charismatic mammal that doesn’t cause problems for people, poached to near extinction. How could humans allow this to happen? It was, truthfully, depressing.

And then I met Zacharia, one of Fatu and Najin’s keepers. A man who spends his life watching and protecting these rhinos, putting his own life on the line to ensure theirs are safe. Zacharia was charming, and completely in love with his charges. He told us all about them, knowing every detail of their history, habits and idiosyncrasies like he would know his own family members. And most of all, he was enthusiastically optimistic about the future, speaking with fervor about how ART will save northern whites. His belief that northern white rhinos would be saved was infectious, and I was cheered and encouraged about the future.

As we said goodbye to the rhinos and their protectors, my faith in humanity was restored, knowing that there are so many smart and dedicated people – from the rangers who protect Fatu and Najin to the scientists working to crack the code on artificial reproduction – who are giving saving this subspecies their all. Fatu and Najin may represent our failures and challenges as a society, but thanks to Zacharia and others, for me they now also represent hope.