2020 State Of The Rhino

The impacts of COVID-19 have been felt across the world. We hope that you and your loved ones are safe and healthy. Our priority remains keeping our staff, field partners and rhinos safe and as such we have put increased protection, monitoring and additional safety protocols in place.

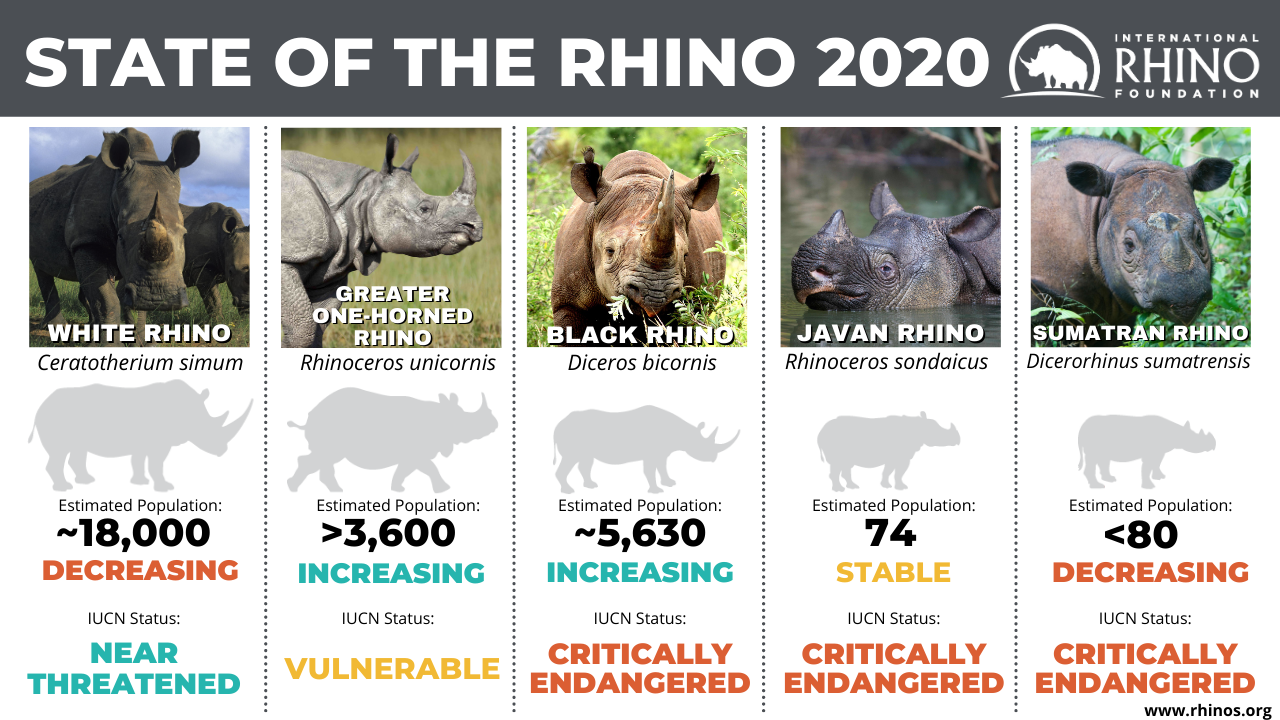

In Africa, rhinos have seen a short term benefit in reduced poaching during the global pandemic. In response to the virus outbreak, countries around the world closed borders and restricted international and domestic travel. With increased military and police presence, regular checkpoints enacted, and government parks and private reserves shuttered to all outside visitors, local poaching gangs found it risky to be on the move without raising suspicions. And the international travel restrictions have closed wildlife trafficking routes to China and Vietnam, the largest black markets for rhino horn.

In comparison, 900 rhinos were killed by criminals in Africa last year, nearly 1 every 10 hours. But this year, South Africa recently reported that poaching dropped from 319 animals in the first half of 2019 to 166 in the first half of 2020. Kruger National Park’s Intensive Protection Zone reported zero rhino poaching incidents in April, the first since 2007.

However, we have grave concerns about COVID 19’s long term impacts on the economy and local communities. As lockdown restrictions are now beginning to ease in many countries, poaching is again on the rise. With the devastation of local economies and widespread job losses, we fear that more people will turn to poaching rhinos and other species.

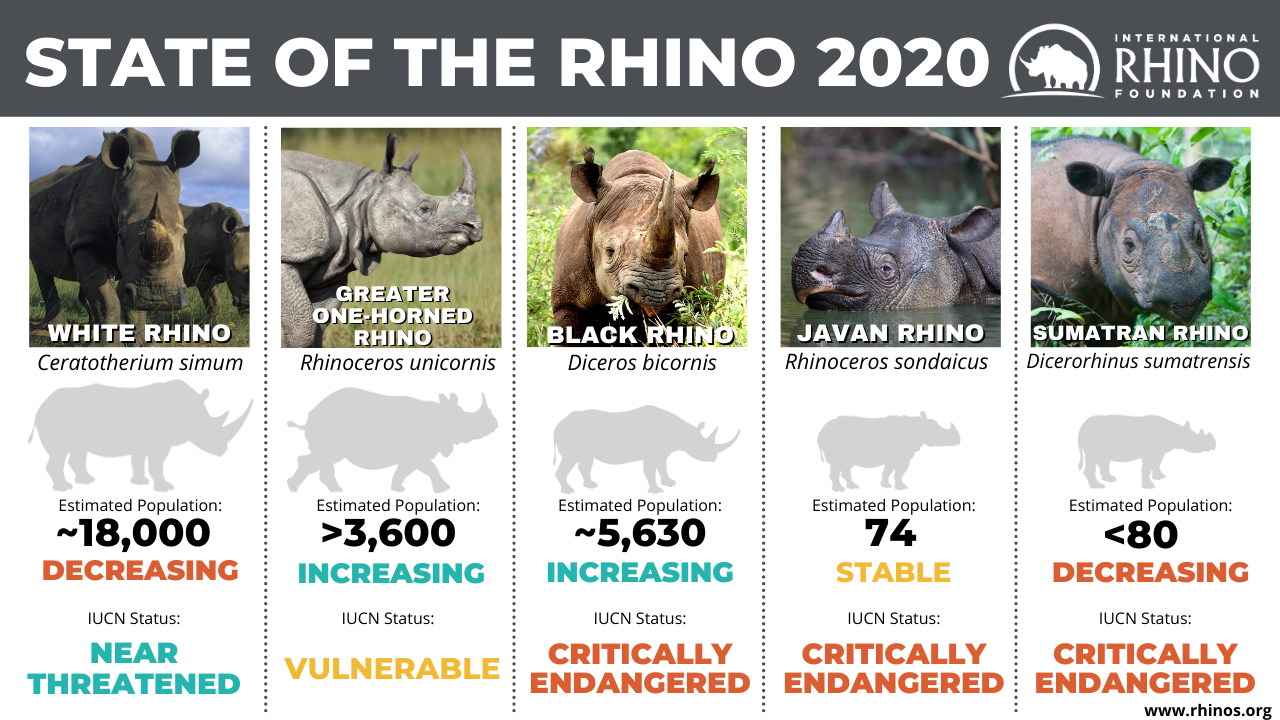

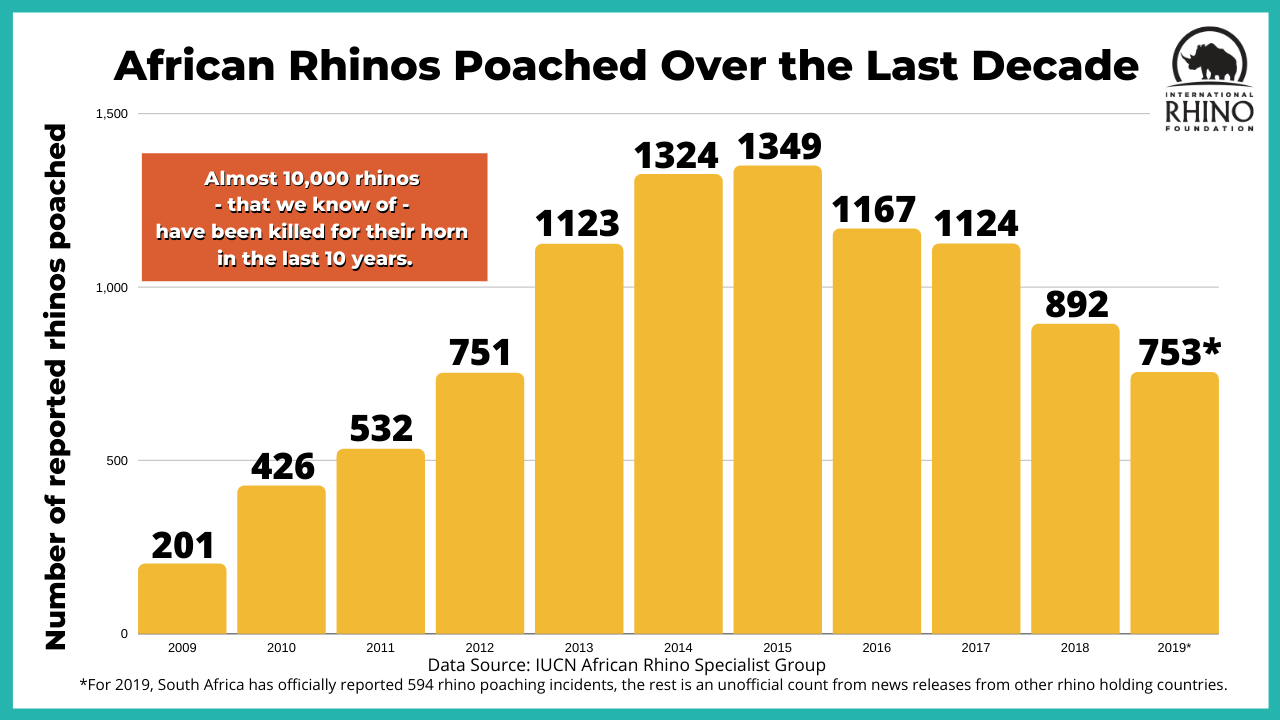

In addition, COVID lockdowns have forced conservationists to postpone planned rhino census operations, which are critical to knowing the status of these imperiled populations. In Africa, fewer than 2,300 black rhinos remained in 1993. The species remains critically endangered at a fraction of the historical population of 65,000. However, in a bit of good news during these tough times, our partners on the ground have reported an increase in the black rhino population from 5,500 in 2019 to 5,630 this year, and the population is expected to continue to make small gains. In some local areas, gains may be higher than expected. Zimbabwe’s Bubye Valley there has been an impressive 13.8% population growth during the first 6 months of 2020.

Africa’s other species, the white rhino, has been facing declines over the last two years due to intensive poaching. The population is estimated to be hovering around 18,000 animals and we’re concerned that the species will continue to face declines this year.

Perhaps the most dire impact of the global pandemic on rhino conservation is the devastating lost of tourism revenue felt by game reserves which are dependent on tourism income for all their wildlife operations. In response to this crisis, IRF established the Reserve Relief Fund this spring to provide gap funding for salaries and equipment for these reserves. We have awarded nearly $250,000 in grants to date to ensure the protection of rhinos continues, and we intend to keep making grants as long as there is need and we have funding.

I’d like to turn to Asia now. In Indonesia, fewer than 80 Sumatran rhinos remain. The species is likely now the most endangered large mammal on Earth, with declines of more than 70 percent in the past 30 years. Three small, isolated populations exist on Indonesia’s Sumatra Island, plus a tiny handful of animals in Kalimantan. The last Sumatran rhino in Malaysia, Iman, died in late 2019.

The Government of Indonesia developed an Emergency Action Plan for Sumatran rhinos in 2017 in response to continued habitat loss and the fragmentation of the population. Going into its third year, the Sumatran Rhino Rescue project, formed by IRF and our partners, has initiated surveys in Way Kambas, Bukit Barisan Selatan and Gunung Leuser National Parks, as well as in Kalimantan in Indonesian Borneo to identify isolated rhinos. The activities are part of a larger plan to rescue rhinos and bring them into large, semi-natural breeding and research facilities like the Sumatran Rhino Sanctuary in Way Kambas to increase population numbers.

COVID-19 has presented hurdles with delays in planned training and rescue options for this year. Timing is critical for these operations, and we are doing all we can to move forward despite the challenges.

Indonesia’s other species, the Javan rhino, made a small gain from 72 to 74 the past year, with two new births just announced! Javan rhinos are found only in Indonesia’s Ujung Kulon National Park, where they are heavily protected. Thanks to strong security measures, there has been no poaching in Ujung Kulon in more than 20 years.

However, illegal fishing and lobster trapping in the protected waters of Ujung Kulon National Park, present both a threat to habitat and the potential that poachers may ‘hitch a ride’ to the beaches of the park which are frequented by rhinos. IRF funded a new marine patrol, which was launched in January of 2020. In the first six months of operations, the two marine patrol units apprehended 45 boats and 218 people illegally encroaching in the park.

As the Javan rhino population increases, expanding their habitat will be a major concern. Habitat management projects are ongoing in the Javan Rhino Study and Conservation Area of Ujung Kulon, including the removal of the ubiquitous Arenga palm, and this opens up corridors for rhinos to move to different areas of the park and promotes new growth of food resources.

In India, the population of greater one-horned rhinos has been steadily increasing to more than 3,600 in India and Nepal from a low of 100 animals in the early 1900s. Nepal planned a census of their rhinos in 2020, but has postponed the count until 2021 because of the impact of COVID-19.

Strict protection by government authorities and forestry officials in India has resulted in several years of poaching declines. There were only three recorded losses in Assam in 2019 and just two incidents so far this year.

As part of the India Rhino Vision 2020 program established in 2009, two greater one-horned rhinos were translocated to Manas National Park in March before COVID-19 related lockdowns.. The transfer brought the population in Manas to 41 animals.

Unfortunately, the final translocation planned for late spring was postponed. India Rhino Vision 2020 was scheduled to wrap up this year with a new strategy envisioned to build on the program’s success, but review and planning meetings have also been pushed back.

The 2020 monsoon season in Assam brought the sixth highest flood ever on record in Kaziranga National Park. 18 rhinos died and hundreds of other wildlife perished during the floods. In response to the widespread devastation and loss, calls for action were intensified and a proposal to build more artificial highlands in Kaziranga has been pushed forward by the government.

We worry that hasty construction of highlands that is not studied and planned scientifically could lead to devastating future changes to the fragile ecosystem. A wrong direction in conservation could derail decades of progress and endanger the greater one-horned rhinos’ continued recovery.

There were also developments in assisted reproduction technologies or ART over the past year. In August 2019 a team of scientists harvested eggs from the two remaining female northern white rhinos, artificially inseminated those using frozen sperm from deceased males and created two viable northern white rhino embryos. With support from the Kenyan Government, the procedure was repeated in December, 2019, and successfully created new embryos, significantly increasing the chances of producing offspring. Last month, additional eggs were harvested from the rhinos and research is ongoing.

The research is part of an effort to save the subspecies from extinction, as well as advance the science of assisted reproduction technology as a tool in conservation of rhino species. Preparations for the next steps are underway with the plan to select a group of southern white rhinos at Ol Pejeta Conservancy from which a female could serve as surrogate mother for the northern white rhino embryo.

Rhinos face many threats from habitat loss, encroachment by people, and fragmented populations that inhibit breeding; however, poaching remains the largest threat to their survival. A decline in the price of rhino horn, which has been trending downward since 2015, has not disincentivized poachers.

Declines in poaching during the global pandemic gives us hope that a stronger commitment by governments in enforcing wildlife crime laws can break up large criminal syndicates involved in poaching, allowing rhinos to maintain steady population gains.

On behalf of the International Rhino Foundation, thank you to our partners, our supporters, and all of you who love rhinos, for helping us conserve rhinos despite the many difficult obstacles this year. Together, we can ensure these marvelous creatures can thrive for future generations.

A full version of the 2020 State of the Rhino is available at https://rhinos.org/state-of-the-rhino/

3 thoughts on “2020 State Of The Rhino”

hi, im doing a speech for school on rhinos and why they are endangered etc.

Do you have more recent state of rhino numbers than the 2020 one I saw on your site?

Also, ‘what can you do to help?’ is a topic i want to cover. What can kids do to help save rhino?

this site is excellent it helped my child in expo project which is for school.thanks to IRF…..

2021 State of the rhino is at https://rhinos.org/about-rhinos/state-of-the-rhino/. 2022 State of the Rhino will be published before World Rhino Day September 22, 2022.