Facing Down a Crisis: How We Almost Lost the White Rhino

When talking about the Southern White rhino (Ceratotherium simum simum), we generally speak of the species as a conservation success story. Remarkably, these animals were brought back from fewer than 100 individuals in the early 1900s to around 20,000 individuals today.

But what led up to that initial crisis point? Why did their numbers get so low and how was their story turned around? And more importantly, how do we apply that success to other rhino species that are in a similar crisis now?

Famous naturalist William John Burchell first saw and documented what he called the “square-lipped rhinoceros” on October 16, 1812.¹ The publication of his description and drawings in 1817 sparked the interest of European hunters, and combined with advances in firearm efficiency, it meant that the White rhino would quickly begin to disappear from many areas in its once extensive range.²

“That the mortality due to man was not negligible is made quite clear by the very few hunters who put pen to paper recording for instance the destruction of eighty animals by two men in one hunting season alone, or the slaughter of eight at a water hole in a single day.”

– from Player and Feely (1960)

For native and European hunters alike, the White rhino became the preferred target over Black rhinos. Due to their social nature, they were often found in groups and were also larger, easier to sneak up on, and less aggressive than Black rhinos. They were not only being hunted for sport, but their meat, skin, and of course their horns, were seen as commodities.

“How this species survived at all is difficult to tell.”²

For 80 years, the uncontrolled hunting of the White rhino saw it wiped out of country after country, until all that existed were between 20 and 100 animals in the territory of Zululand- now known as the KwaZulu-Natal Province of South Africa.

In 1895, colonial conservationists were able to convince authorities to establish Africa’s first protected conservation area, the Umfolozi Junction Reserve (today known as Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park) with the specific intent of saving the White rhino. Here, the White rhino was declared to be royal game and finally received legal protection from hunting.³

The White rhino was mostly safe in this small pocket and by the 1950s, the population had grown to over 400. But it was a slow growth, and they survived in only a fraction of where the species once lived.

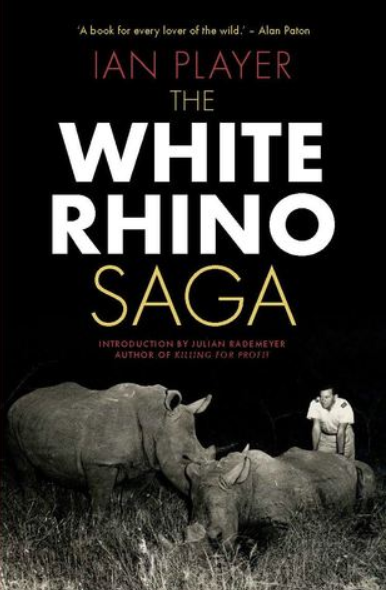

In 1960, conservationist Ian Player launched “Operation Rhino,” translocating groups of White rhinos to protected areas throughout their historic range. He knew that expanding their range outside of Umfolozi would give them the best long-term chance for recovery and accelerate their growth even more.³ This massive undertaking has the late Ian Player credited with the recovery of the White rhino species as their population grew every year since Operation Rhino until 2012-2013, when poaching deaths started outnumbering rhino births.

Without the efforts in 1890s, and the continued work and increasing government protections over the last 80 years, the White rhino could have very easily slipped through our fingers and gone extinct.

Today, we are facing down a new crisis as we are uncomfortably close to losing not one, but three rhino species. Each species and their habitats are unique and the conservation strategies have to be tailored to each one. The White rhino and Greater One-Horned rhino still need protection to keep their numbers healthy but we are taking what we can from their success stories to save the Black, Sumatran and Javan rhinos from extinction.

Your support makes it possible for us to continue to protect all five rhino species.

“Conservation is not a plaything, or a luxury, or something new.

It is survival.”

– Ian Player

All of the below articles (and many more) can be found at the Rhino Resource Center, the World’s Largest Rhino Information Website.

[1] Cave AJE (1947). ‘Burchell’s Rhisocerotine Drawings.’ Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London 159(2), 141-146.

[2] Player IC, Feely JM (1960). ‘A preliminary report on the square-lipped rhinoceros Ceratotherium simum simum’. Lammergeyer 1, 3-23.

[3] Brooks S (2006). ‘Human discourses, animal geographies: imagining Umfolozi’s white rhinos.’ Curr. Writ., Durban 18, 6-27.