How Science is Being Used to Secure a Brighter Future for Black Rhinos in Namibia

This blog was written by IRF partner, Minnesota Zoo Foundation

The International Rhino Foundation (IRF) supports rhino conservationists and scientists around the world. In 2023, the Minnesota Zoo Foundation received an IRF Research Grant to strengthen management for the world’s largest meta-population of black rhinos by conducting a population viability analysis. Read more about their project and its impact on black rhinos in the blog, written by Minnesota Zoo Foundation staff, below.

Namibia’s black rhino story is full of superlatives:-The single largest population, the last truly wild population, the oldest conservation organization dedicated to black rhino conservation (Save the Rhino Trust, SRT, established in 1982), and one of the longest-running individual databanks for a rhino population. SRT’s Rhino ID kit – as it was called back then – was created for the free-ranging black rhino population surviving in the remote northwest region of Namibia back in the late 1980s. Over the years, it has advanced from printed photos in a photo book to a Microsoft Access database to now fully captured in SMART Conservation software. The effort inspired others in the country to follow suit and by the late 1990s, several of Namibia’s black rhino ‘custodians’ (private individuals holding the government’s rhinos on their property) were keeping track of individual rhinos.

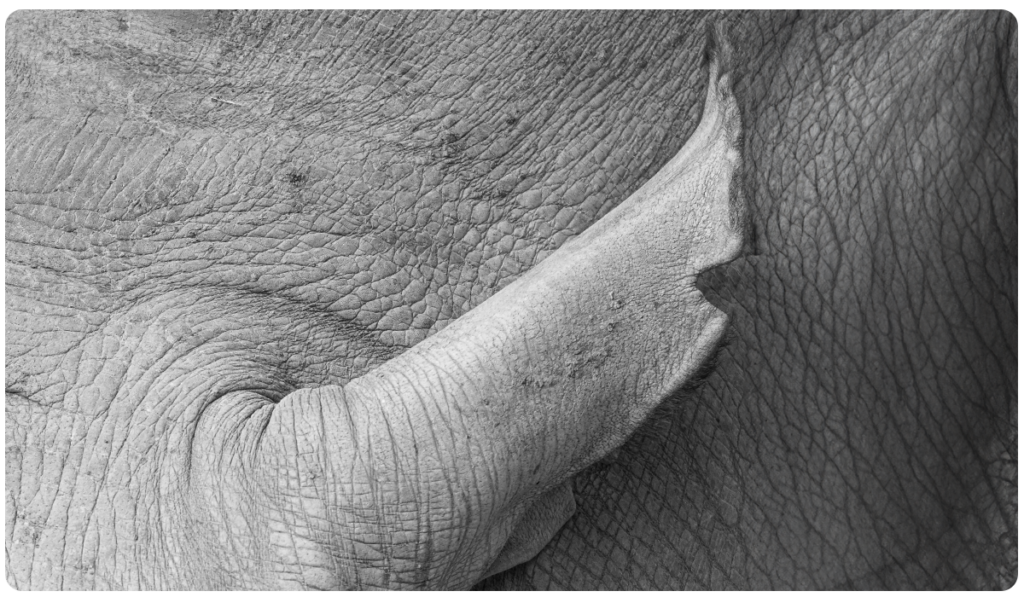

How did they do this? Individual rhinos are reasonably easy to identify based on unique visible features such as their horn shape or earmarks. Most useful are the marks on their ears, which can be both natural marks and human-made notches given to them when they are captured, like an ear piercing. When observed with binoculars or examined on an image captured by a digital zoom camera, these features provide conservationists with the information to attach an identification (i.e. name) to each rhino sighted.

Over time, this information can help tell a story about each rhino’s life. Known as a life history, conservationists can learn vital knowledge about their sex, birthday, when they leave mom, when they give birth (if they are female) and when they die. Over even more time, multi-generational family trees can be created that provide even greater insights into how well a particular population of rhinos is doing. Conservationists learn critical insights about the population, such as what rate it is growing or shrinking, what age classes of rhinos seem to be doing better or worse, and even what other factors might be influencing these processes.

While all this knowledge is useful to have, how can it help save rhinos? Beyond simply knowing the health of the population, scientists have developed techniques that can take greater advantage of this information by using it like a ‘crystal ball’ to predict the rhino’s future – or specifically what is the likelihood of the population going extinct under different possible circumstances. These circumstances might be threats such as poaching. They might also include protection strategies such as moving rhinos to establish new populations or supplement existing ones. This technique, called population viability analysis, or PVA for short, has been practiced by a small but influential specialist group of scientists operating under the International Union for Conservation of Nature, called the Conservation Planning Specialist Group (CPSG), since the 1980s.

In 2023, with support from the International Rhino Foundation, Namibian rhino conservationists invited CPSG to facilitate the first black rhino PVA in Namibia. The team, including 4 rhino conservationists from Namibia and 2 scientists from the USA, joined forces to bring together their knowledge – and long-term rhino data recently published in the journal Oryx – to explore how the future might look for several of Namibia’s key black rhino populations. The team examined scenarios like what might happen if poaching gets worse, or the climate gets hotter and drier (as it’s predicted to), and even how long it might take to grow a new rhino population. What we found was quite interesting. Most of the rhino populations had low extinction risk when only drought persisted. However, when poaching was added, especially at moderate to higher rates, population extinction risk rose dramatically for most of the populations. More interesting was the predicted growth for a new rhino population that it could reach between 500-800 rhinos by 2070 even under current drought conditions and moderate poaching rates. This could eventually rival the world’s largest black rhino population!

Only time will tell the true fate of Namibia’s black rhino. Yet this latest initiative has shown that harnessing evidence from the hard work of rangers on the ground with cutting-edge science could help secure a brighter future for rhinos by helping guide critical decisions by those given the demanding task of ensuring their protection.